Working on an Android tablet: first six weeks

I’ve been working full time on my Android workstation for over a month now, and it is time to write an update about it. How has it worked out?

What I’ve been doing

I would love to tell stories of working from parks and cafes, like Mark O’Connor has on his iPad setup, but unfortunately we had a backlash of winter here in Berlin and the warm spring weather only came back this week.

Instead — quite atypically — I’ve been mostly desk-bound in this time. The EU projects that mandated a lot of travel have now ended, and my current projects are more about software development than evangelism.

But that actually makes this experiment even more useful, as it means most of the six week has been actual programming, which is what most of my readers also do.

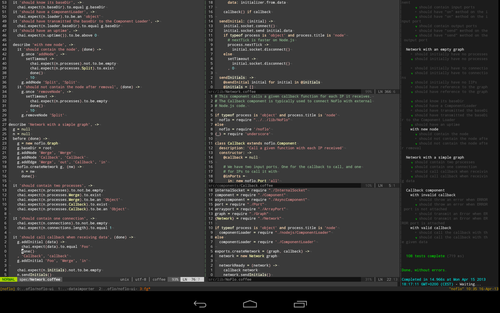

For those who missed my setup in the previous post, this is how it looks in action:

On-screen are tmux, vim, and a Grunt test automation watcher running inside a MOSH client.

Here are some things I’ve done in the last month:

- Porting the NoFlo flow-based programming engine to run in both browser and Node.js with the same codebase, including a tutorial on how others can do the same

- Writing and publishing an implementation of Android-style Action Bars for web apps

- Adding multiple major features to the web-based NoFlo IDE

- Dealing with the issues raised with the release of jQuery UI 1.10 and Backbone 1.0.0 with Create.js and VIE

- Blogging, including publishing some quite popular posts

In general the experience has been a positive and productive one. I’ll write about some nuances here.

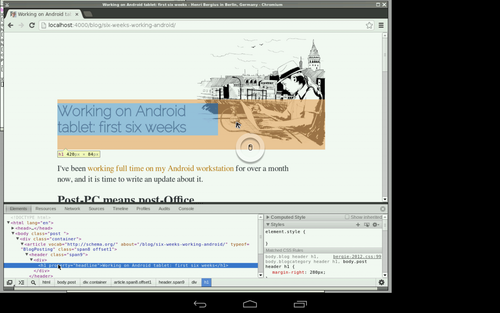

Web debugging

As you can see from the list above, much of my recent work has been client-side. With this, the unavailability of web debuggers on mobile browsers can become a problem.

I’ve tackled this issue in two ways:

- More tests. Instead of poking around in a debugger, I try to write Mocha tests for most aspects of my applications. This also has the benefit of automation, meaning that PhantomJS will test everything in my application every time I commit

- VNC and desktop browsers. When I really need one, I can still use the web debugging tools of traditional web browsers via VNC

See Mark O’Connor’s setup instructions for VNC on one of these tablet workstation setups.

Post-PC means post-Office

One area where tablets are really lacking is support for traditional office tools like word processors and spreadsheets. There is a Google Drive client, but it is very slow (even small spreadsheets can take minutes to load) and mostly non-functional (word processor doesn’t even support headlines).

There are also some other office suites available, but even these are better used for viewing documents than actually making changes to them.

But the bigger question is whether traditional office tools even have a place in this modern world. The commentary on constant delays with Microsoft Office for iOS and Android shows that people don’t see them as that relevant any longer:

For the longest time, Office was the ubiquitous productivity suite. Everybody used it. Nobody considered using anything else. However, since this mobile revolution started, even non-geeks are starting to question whether Office is still all that. I had breakfast this morning with a CPA who does all of his work in Google docs. There is an entire generation of future workers going through high school and college now who don’t even have Office installed on their computers. If Microsoft has any hopes of keeping Office relevant, it needs to be everywhere, including the iPad.

Personally, I might be a lot better off writing my documents in Markdown, versioning them with git, and maybe using custom data-gathering applications with CouchDB map-reduces for data visualization.

The story of tablet productivity is still evolving. The new tools and interaction techniques we have will eventually give rise to new kinds of productivity applications. That may signal the end of the Office hegemony.

Presenting from the tablet

On the first week of this experiment I was actually traveling. The final review meetings for both of the EU projects were being held in Brussels and Luxembourg, and I had to present our results.

As the presentation tools on Android are not very good, I took this as an opportunity to finally start using an HTML-based presentation system. For this, I picked DZSlides, with a custom Jekyll-based flow for constructing slide decks from individual assets stored in git.

The results are quite nice, and I love being able to embed live demos inside the slides.

With every computing platform, there is always some fiddling involved with getting your device connected to a beamer. I was positively surprised with how easily the Nexus 10 worked. Simply connect using a micro-HDMI to VGA adapter, and you’ll have the tablet screen up on the projector.

Minor annoyances

Everybody knows about the common gripes with Android on large tablets — most apps have been written with a narrow phone screen in mind, and simply look bad on a wide 10” screen. Twitter is a good example of the typical neglect of Android’s UI guidelines.

Somewhat surprisingly, this even applies to Google’s own tablet applications. Apps like Google+ and Google Drive are a lot more functional on an iPad than on a large Android tablet.

However, these are more of a problem when using something like my Nexus 10 as a media tablet, and don’t really affect how well it works as a programming workstation.

For programming work, what matters is things like the beautiful screen, Android’s reasonably good support for hardware keyboards, user-accessible file system, and the ability to share information between applications. These are the main reasons why I went with Android instead of an iPad.

However, not all is sunshine. So far, the main annoyances for me have been:

- Regressions in Magic Trackpad support mean that it is practically unusable when you also have a Bluetooth keyboard. A lot of character presses get duplicated, making typing near-impossible. I’m assuming other mouse devices would however work

- MOSH ConnectBot — which I’m using for my programming sessions — makes Ctrl and Esc keys not work. Luckily I was able to find a workaround

- Android 4.2.2 is buggy on the Nexus 10. Especially Chrome can cause the system to crash. Other browsers help here, and hopefully Google will fix the issue soon

Now, crashes and freezes may sound like a big deal. But thanks to using tmux, they just mean a short interruption, and not any lost work. I just restart my tablet or MOSH client, attach back to the tmux session I was working with, and I’m right back to where I was, cursor position, vim splits, and all.

Quantifying productivity

Calculating programming productivity is notoriusly difficult. While Mark was able to show impressive figures from his iPad setup, I don’t have anything similar because:

- I haven’t had the time to crunch the numbers on the work I do

- The ending of the EU projects meant that I’m now doing different things than I did with my laptop, and so comparing results from the two is hard

And in the end what matters more is the results of the work, not the effort spent getting there.

But still, it would be good to have a bit more data on how well the setup works besides the subjective “it feels like a good way to program”.

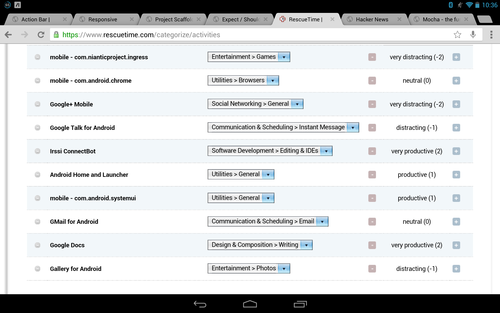

To this end, I recently started using the RescueTime tracker on both of my Android devices. It keeps calculates how much time I spend with different applications each day, and even allows me to give some sort of productivity scores for them:

I’ll be running this for a while, and will try to combine it with some statistics from my GitHub account. Those two should be able to paint a picture of how I work.

Conclusions

In the beginning, like with any new tool you have to start using, the Android tablet setup felt weird and limiting. But it has grown on me since, and right now I’m not regretting giving my laptop away.

But at the same time, if a new interesting device came out, the cost of switching to that would be minimal. After all, the Nexus 10 for me is essentially just a window into the web and my terminal running somewhere else.

In a way this decoupling is similar to the traditional desktop PC setup where you have a separate computer, screen, mouse, and a keyboard. The difference here is that none of those parts are bound to a desk or connected with cables. Instead, the peripherals talk with my screen over Bluetooth, and my screen with the “computer” over the Internet.

If I for instance want a better keyboard, I can just buy one and replace that part without having to change anything else with my setup.

Cost advantage

One aspect that people have remarked on is cost. Over the course of two years — which is the typical replacement cycle of a professional workstation — this setup is cheaper than a MacBook Air. And with that price I get a lot better screen and about double battery life, and even a smartphone.

What I lose is the ability to work fully offline, though somewhat alleviated by having local vim and git via Terminal IDE.

Moving forward

The experiment will keep continue. In these six weeks, I haven’t seen any negative impact on my productivity from working on an Android tablet instead of a laptop, and many positive ones. Portability, battery life, and the emphasis on tests and automation are probably the foremost.

Of course, new devices come to the market, and eventually something will come that beats the current setup. But then I’ll be able to switch without even losing my cursor position, so the only cost is the hardware itself.

In time, I will write more about how things are going.

Update: Read my Working on Android, 2017 edition post.