Writing reusable, multi-platform JavaScript with Component

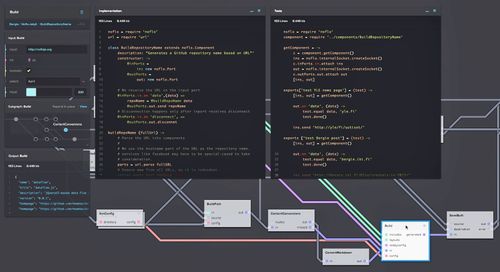

I’m currently in the process of porting the NoFlo Flow-Based Programming environment to run also in the browser. While there are some obvious differences in things like filesystem interaction and component loading, the goal here is to reuse as much of the same code as possible between these two platforms.

Many of the building blocks are already in place, and so the port should be complete still this week. You can track the work in issue 63.

Update: the post below is mostly of historical value. Nowadays I would recommend using NPM for dependency management and Webpack for browser builds. For NoFlo, grunt-noflo-browser provides automation for this.

A fragmented ecosystem

The current client-side JavaScript ecosystem is quite fragmented. While on general level any code can be used anywhere, there are many different approaches at packaging, code loading, and templating. In many ways this resembles the PHP landscape before Composer solved the problem there.

On Node.js we haven’t had this problem for a while, as NPM provides an excellent way to share and install code. With more than 27000 modules available, it is truly the default solution for JavaScript package management server-side. Some frameworks like Meteor tried to deviate from this by introducing their own package managers, but eventually came back to the fold.

Module definitions

There are many different ways for handling loading and encapsulation of JavaScript code. The module pattern is quite popular building block. Many also expose their code as jQuery plugins even though that really only makes sense or DOM handling.

Here is how you would define a jQuery plugin:

(function ($) {

$.fn.somePlugin = function () {

// some code here

};

})(jQuery);

Some efforts towards standardization have been made, including the Asynchronous Module Definition spec, and the synchronous CommonJS module spec that Node.js also uses.

Here is how an AMD wrapper for code looks like:

define('somePlugin', ['jquery'], function ($) {

return function () {

// some code here

};

});

The CommonJS definition for something similar would be the following. This will look familiar to Node.js developers:

var $ = require('jquery');

exports.someFunction = function () {

// some code here

});

Harmony is the proposed next generation of the JavaScript language, and it includes a new module syntax:

module 'myModule' {

import 'jquery' as $;

export function someFunction () {

// some code here

}

}

It is no wonder many developers feel a bit lost on how they should expose their code or widgets!

The Harmony module spec may eventually harmonize this, but it will take a while before you can actually ship code like that for even a reasonably majority of browsers.

Module installation and loading

Once you’ve picked the module pattern to follow, the next question is how to actually get your dependencies installed.

The traditional way is to fetch “known good” versions of the libraries, add them to your project repository, and then just include each library with its own script tag. But this means having to maintain all the libraries in your own project, and cluttering your repository and change log with them.

A variant of this is loading common libraries from a Content Delivery Network like Google. This has the advantage that your users won’t have to download something like jQuery separately from each web server, and that you don’t need to duplicate the library files in your own code repository. But at the same time, this relies on the CDN provider not breaking things, and complicates offline usage.

And you still have to write script tag for each of them.

Bower

Twitter’s Bower package manager aims to help with dependency management. You declare the libraries your code needs in a component.json file, run Bower, and you’ll get the correct versions downloaded to your system.

Bower only handles dependency resolution and downloading, and so you’ll still be writing script tags for all modules you installed. But at least this allows you to keep the library files out of your repository.

Require.js and volo

The Require.js project seeks to solve this by handling module loading for you in an automated manner. They even provide the volo package manager for installing all the libraries you need.

Require.js is a quite popular way of solving this, but means that you will need to follow the Asynchronous Module Definition specification with your code.

Component

Component is a newer solution for this started by TJ Holowaychuk of Express and Mocha fame.

The system is explained a lot better in the introductory blog post, but in nutshell Component is a combination of a package manager and a module loading system based on CommonJS.

With Component you can easily write and distribute reusable JavaScript modules, including user interface components that may include HTML templates and CSS. There is a component writing tutorial available.

The Component installer will pull all the dependencies for you, and construct a single, easy-to-include JavaScript file out of them and your own code. If you want to think of it in that way, this is sort of similar to Composer generating an autoload file for PHP code.

Which to choose?

Given the multitude of options available, it can be hard to choose which one to go with. Eventually a winner may emerge, but in the meanwhile, my approach is the following:

- Component for client-side libraries and widgets

- NPM for Node.js libraries

If I was just writing client-side code, Require.js and volo may have been just as good option, at least if I want to deal with AMD.

However, the big advantage of Component is that it is based on CommonJS modules, which Node.js also uses. With it, I can share library code a lot more easily between browser and the server, the two main platforms of the Universal Runtime.

CommonJS modules run nicely in the browser, on Node.js, and other server-side JavaScript runtimes.

Writing a multi-platform library

Writing widgets with Component is covered nicely in the building a date picker component tutorial, and so I’m focusing on how to build more general-purpose libraries here.

Getting Component

The first step with Component is getting the tooling in place. Component — like most of the JavaScript dependency managers — is written on top of Node.js. It would be possible to implement the Component spec in other languages for easier integration in their native toolchain, but for now Node.js is what you must install.

Once you have Node.js running, getting the Component tools is easy:

$ sudo npm install -g component

This will give you the component command. You can run it to see the functionality it provides.

Finding dependencies

The next step is to find the libraries you need. Quite a lot of libraries and widgets are already available, and can be found from the Component Wiki.

You can also use the Component command to look up modules:

$ component search underscore

component/underscore

url: https://github.com/component/underscore

desc: JavaScript's functional programming helper library.

nathan7/memoize

url: https://github.com/nathan7/memoize

desc: underscore's memoize

As you can see, the components use a “GitHub-like” naming scheme of <vendor>/<module>. This is again similar to vendor names in Composer:

The package name consists of a vendor name and the project’s name. Often these will be identical - the vendor name just exists to prevent naming clashes. It allows two different people to create a library named json, which would then just be named igorw/json and seldaek/json.

Since NoFlo relies heavily on Node’s event API, we need to find an equivalent library for Component. After a quick look through component search events, it turns out component/emitter does the job.

The component.json file

Each Component module must provide a component.json file where you declare things like the name of the package, the version number, the software license, the files provided, and the possible dependencies. This is quite similar to the package.json file in NPM.

I’m using a very simplified version of NoFlo’s Graph class as the example here, so I can call the library bergie/graph. Like most JavaScript libraries, this will be under the MIT license.

{

"name": "graph",

"repo": "bergie/graph",

"description": "Simple graph class",

"license": "MIT",

"version": "1.0.0",

"scripts": [

"graph.js"

],

"dependencies": {

"component/emitter": "*"

}

}

For Node.js support you’ll also need a corresponding package.json file:

{

"name": "graph",

"description": "Simple graph class",

"main": "./graph.js",

"version": "1.0.0"

}

Once the dependencies are declared, run the installation:

$ component install

The example only uses Node.js’s built-in libraries, so NPM installation is not yet needed. If you add third-party libraries, you need to install them also:

$ npm install

Module code

Writing a Component module is very similar to writing Node.js modules. Create the file we just declared in the JSON file and open it in your favourite editor.

Since we’re aiming for multi-platform code, the main difference is dealing with platform-specific differences. For example, the event emitter library in Node.js is called events, and the Component equivalent is called emitter.Luckily their APIs are exactly the same, so we only have to do loading conditionally:

var EventEmitter;

if (typeof process === 'object' && process.title === 'node') {

// Node.js

EventEmitter = require('events').EventEmitter;

} else {

// Browser

EventEmitter = require('emitter');

}

This way, we have the correct event emitter implementation available for our code. Now we just create a constructor function to inherit from that:

// The constructor, just call "super"

function Graph () {

this.nodes = [];

EventEmitter.call(this);

}

// Set up inheritance

Graph.prototype = Object.create(EventEmitter.prototype);

// Define methods

Graph.prototype.addNode = function (name) {

this.nodes.push(name);

this.emit('node', name);

};

Once the code is there, we need to expose it as a CommonJS module:

module.exports = Graph;

Running the module in Node.js

For Node, this is all we need to do to be able to use our Graph as a module:

// Include the module

var Graph = require('./graph');

// Instantiate

var g = new Graph();

// Hook into events

g.on('node', function (name) {

console.log("Node added " + name);

});

// Call a method

g.addNode('Foo');

Running this should end up with message Node added Foo shown on the console.

Running the module in browser

To be able to run the module in the browser, we need to run Component’s build process.

$ component build

This will generate a JavaScript file build/build.js which provides CommonJS module loading support, and all the JavaScript code we’ve declared in the JSON file.

Now you can include that file in your HTML, and start using the Graph module:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<script src="./build/build.js"></script>

<script>

var Graph = require('graph/graph.js');

var g = new Graph();

g.on('node', function (name) {

alert("Node added " + name);

});

g.addNode('foo');

</script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

Conclusion

Component can be used for solving the JavaScript code-sharing problem. They let you build full applications out of smaller, reusable modules. And thanks to the CommonJS module specification, it is quite easy to write these modules in away which enables them to be used also under Node.js and other JavaScript runtimes.

This post, and the date picker tutorial should give you enough information needed for starting to decouple your front-end applications, and to participate in the emerging open source Component ecosystem.

Even with more than 800 components available, it is too early to declare Component the winner in the front-end dependency management space, but it is a well-designed system that works quite well.

I will be utilizing Component for some of my JavaScript projects in the future.