Neutron Protocol: Separating UI from the CMS

At the moment the prevailing wisdom is that each CMS should have its own user interface, and that user interface should be web-based. But there is also another way: separating the user interface from the CMS using a CMS-neutral protocol called Neutron.

According to Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the earliest web browser was also an editor. And the late 90s Netscape Communicator followed this ideal by including a HTML editor that could publish changes to pages using the HTTP PUT method. But then the idea of editing via the web browser transformed to clunky forms and Java applet -based WYSIWYG editors, brought about by the rise of content management systems.

The problems of the user interface being part of the web page were multiple: it cluttered the produced HTML, it was possible to break by layout changes, sometimes the login and editing options were hard to find. It also meant that each and every CMS would have a completely different user interface. A problem made especially difficult if you had to use multiple systems. For example:

If you are Quim Gil, working for Nokia's maemo.org, you're living in a world of many, many CMSs. The marketing and community parts of the website are run by Midgard, the documentation wiki by MediaWiki, your own blog by WordPress, and the list goes on. While in this kind of corporate setup it has been possible to mostly unify usernames and passwords, it still means each part of your work runs with different UIs, and different usage logic. Back in 2003, I named this syndrome Frankenstein CMS.

In addition to consistency and usability, offline editing has been a big issue with most CMSs. In typical situation, it simply doesn't exist, making copy-and-paste way of taking documents with you to edit on a laptop while traveling.

There have been several initiatives in solving these problems. A quite limited, but so far successful example is the Universal Edit Button specification, making rounds earlier this summer. The idea is that CMSs would include metadata on where the editing view of a particular page was in the page itself, and then browsers would display a button leading to it. The approach has been adopted by several big players, including Wikipedia, and we also made it a part of the new CMS that will be built on Midgard 2:

Another, also somewhat limited example is the MetaWeblog API provided by most blogging platforms. It has enabled vendors to produce great offline blogging software like Ecto and MarsEdit that provide offline editing and work with almost any blogging system out there. As I write this, I'm using Ecto on my MacBook Air, and will later use it to publish this entry to my Midgard server. The Atom Publishing Protocol will likely be the successor of MetaWeblog, but appears to still keep the blog-only focus.

Back in the earlier days of OSCOM we had another initiative called Twingle. It was a XUL-based desktop CMS client that utilized WebDAV and some XML introspection files to edit and publish data on different CMSs. After a March 2003 OSCOM Sprint in Zurich we were able to demo the same client browsing and editing resources on three CMSs, including Zope and Midgard. Unfortunately, then CMS market became so hot that vendors were simply too busy to pick this up and the project died.

Luckily Michael Wechner, of OSCOM and Apache Lenya fame didn't let the idea die. He worked it onwards, naming the protocol used for conversation between the client and the server Neutron Publishing Protocol, a play on Atom. He also built a new client, Yulup, as a Firefox extension that could manage content on compatible servers.

In summer 2007 I saw a demo of Yulup and discussed Neutron with Michi and was impressed. But was back then too depressed by the Czech episode and other personal issues to press on with the idea. Having watched another year of the directions the community is taking Midgard CMS to, and how clients view CMS deployments, I'm starting to think the time would be ripe for going full forward with Neutron.

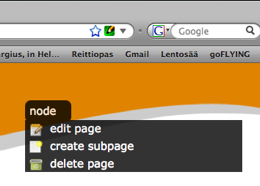

In nutshell Neutron is a metadata layer that allows a CMS to specify the actions user can take, and the methods provided for those actions. The methods can either be full-blown WebDAV, or simpler GET-and-POST that more limited CMSs can support. Neutron also provides its own authentication mechanism, though I would gladly see that overtaken by a more secure and widely supported standard like OAuth.

Widely-supported Neutron would provide huge advantages: letting the developers of a CMS to focus on the actual management and presentation layers of the system, and allowing more innovation to happen in the client end due to combined efforts from multiple CMS projects. It would allow building of different content management interfaces for different audiences or usage scenarios. Simple editing and publishing clients that could run fully in browser's AJAX space for casual bloggers or wiki editors, workflow tools for gatekeepers of corporate publishing processes, and full-blown desktop content management tools for site editors. Other special cases like mobile content management could also be provided for.

So what is needed for this future to become reality? First of all, we need to make CMS developers aware of the possibility. Then we need a killer client that every CMS provider would want to support. And then we can expand the protocol, and build additional clients to cater for special needs.

The big question is how this will happen. Industry groups in CMS space are loose or non-existing, and so they lack the muscle to push any standards. Effort by single CMS vendor would probably stay partisan, as developers of different systems are quite suspicious or ignorant of each other. But maybe a combination of the two would work: industry group, such as OSCOM organizing some compatibility hacking events for the developer community, and a company dedicated at building a killer client application. It warrants serious consideration if Nemein should be that company.

This manifesto on transforming how CMSs are used was written in an Eurostar London-Brussels train, sipping Dourthe's Bordeaux white and listening to the Karelia cycle by Sibelius.